Lexical Repetition, Narrative Architecture, and Covenant Movement in Genesis

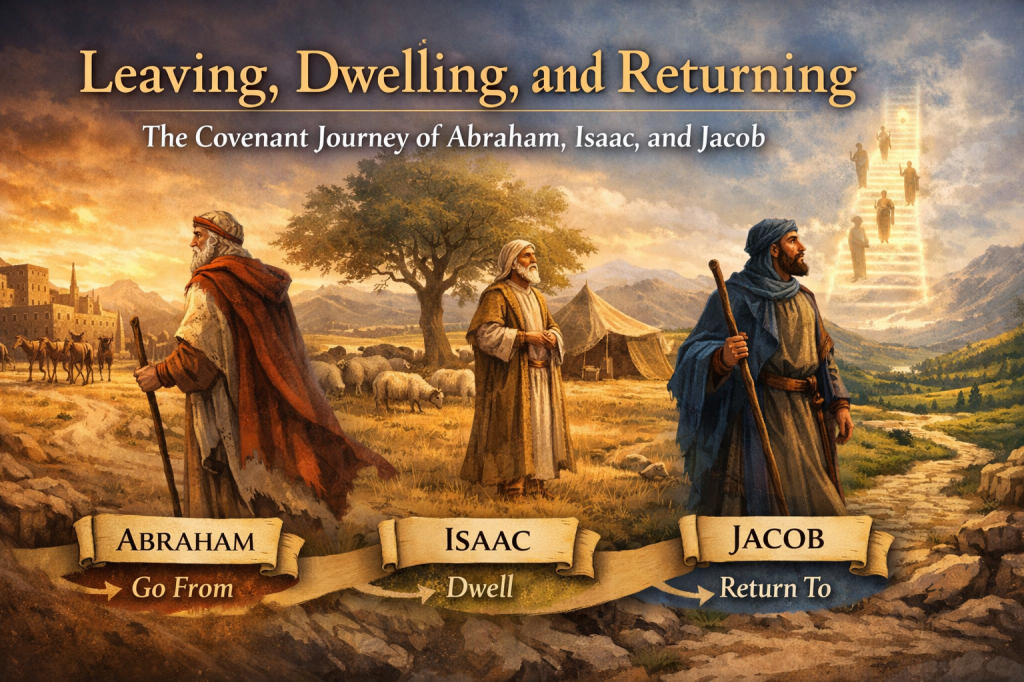

The apparent tension between God’s command to Abraham to leave his land and kindred and God’s command to Jacob to return to his land and kindred is not a loose thread in Genesis. It is a carefully woven feature of the narrative. When read in isolation, these commands seem to pull in opposite directions. When read within the literary and theological architecture of Genesis, however, they reveal a coherent pattern in which obedience is shaped by the historical movement of the promise.

Crucial to seeing this coherence is the often underappreciated role of Isaac. Isaac occupies a pivotal structural position in Genesis, functioning as the connective tissue between Abraham’s departure and Jacob’s return. This positioning is not accidental. It is one of the narrative’s most deliberate theological devices.

Shared language and covenant movement

The lexical overlap is unmistakable. Abraham is commanded:

לֶךְ־לְךָ מֵאַרְצְךָ וּמִמּוֹלַדְתְּךָ וּמִבֵּית אָבִיךָ

Go for yourself from your land, your kindred, and your father’s house (Gen 12:1)

Jacob later hears:

שׁוּב אֶל־אֶרֶץ אֲבוֹתֶיךָ וּלְמוֹלַדְתֶּךָ

Return to the land of your fathers and to your kindred (Gen 31:3)

The repetition of ארץ and מולדת is deliberate. Genesis wants the reader to hear the echo. Yet the direction of movement has reversed. Scholars have long argued that this reversal signals not contradiction but covenantal development. The same God speaks, using the same vocabulary, but the promise has advanced.

What counts as faithful obedience is therefore not fixed to a single posture toward land or kin. It is indexed to the stage of redemptive history. Abraham leaves because the promise must be disentangled from inherited structures. Jacob returns because the promise now demands settlement, confrontation, and continuity.

Isaac as the narrative hinge

Isaac’s role clarifies why this reversal makes sense. As A. B. Luter and S. L. Klouda observe, Isaac serves as the hinge connecting the Abraham and Jacob narratives while advancing the theme of patriarchal blessing and providing the genealogical bridge between Abraham and Israel. His narrative presence is structurally restrained but theologically decisive. See Luter and Klouda, “Isaac,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch, 447.

What is striking is how the promise to Abraham resurfaces at the close of each patriarch’s life. This repetition creates a rhythmic reinforcement of covenant continuity across generations. The language of blessing (ברך) dominates the Isaac material, marking him less as an innovator and more as the bearer and conduit of promise. Isaac does not redirect the covenant. He stabilizes it.

This stability is precisely what allows Jacob’s story to unfold as it does. Without Isaac, the narrative would leap too quickly from departure to return. Isaac slows the story down. He ensures that the promise is not merely spoken but inhabited.

Narrative symmetry and inversion

The sophistication of the narrative architecture becomes clearer when viewed synoptically. Scholars have noted mirror-image symmetry between the Abraham-Isaac and Isaac-Jacob cycles, forming concentric literary units. James M. Hamilton Jr. sharpens this observation by showing that the Abraham and Jacob narratives function as inversions of one another. Abraham is called from Haran in the east to the land of promise. Jacob is sent from the land of promise to Haran in the east. See Hamilton, Typology: Understanding the Bible’s Promise-Shaped Patterns, 345.

The inversion is not merely geographical. Abraham receives divine promises without negotiation. Jacob, by contrast, places conditions on God in his Bethel vow. Everything in Jacob’s story runs backward. Yet this inversion does not undermine the promise. It tests and exposes the character of the heir who must now carry it.

Isaac’s presence between these narratives is what makes the inversion intelligible rather than chaotic. His life represents continuity without forward momentum, inheritance without expansion. In narrative terms, he holds the covenant in place so that it can be contested again in Jacob’s generation.

Crisis, promise, and generational focus

Isaac’s narrative also sustains the recurring crisis-tension-resolution pattern that structures Genesis. The threatened seed, the vulnerability of land, and the uncertainty of blessing reappear through motifs such as barrenness and displacement. These tensions correspond directly to the three covenant promises of seed, blessing, and land.

Yet the generational emphasis shifts. Abraham’s narrative foregrounds the promise of an heir. Isaac’s narrative preserves that promise. Jacob’s narrative presses toward land occupation and permanence. K. A. Mathews notes that God’s promise at Bethel sustains Jacob’s hope during exile and becomes the theological engine driving his eventual return. See Mathews, Genesis 11:27–50:26, 1b:370–71.

Jacob does not return because home is safe. He returns because promise demands embodiment. The land that Abraham left and Isaac dwelt in now requires Israel to wrestle, settle, and endure.

Conclusion

When Isaac is restored to his proper narrative role, the logic of Genesis sharpens considerably. Abraham’s departure, Isaac’s dwelling, and Jacob’s return are not competing models of obedience. They are successive movements in a single covenantal drama.

Isaac’s life functions as the theological and literary mechanism through which God’s promise moves from initiation to habitation to expansion. The reuse of land and kinship language across generations is not a problem to be solved but a signal to be read. Genesis is teaching its readers how obedience changes when the promise moves forward in time.

The God who commands departure is the same God who commands return. What changes is not God, nor the promise, but the moment in which faith must be lived.